- Home

- Dave Grohl

The Storyteller

The Storyteller Read online

Endpapers

Courtesy of the author’s personal archives

Courtesy of Magdalena Wosinska

Dedication

FOR VIRGINIA GROHL.

Without her, my stories would be very different.

FOR JORDYN BLUM.

You made my story so much more exciting and beautiful.

FOR VIOLET, HARPER, AND OPHELIA.

May each of your stories be as unique and as amazing as you are.

Contents

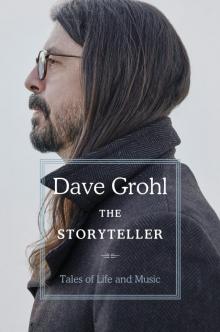

Cover

Endpapers

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction: Turn It Up

Part One: Setting the Scene

DNA Doesn’t Lie

The Heartbreak of Sandi

The Scars Are on the Inside

Tracey Is a Punk Rocker

John Bonham Séance

Part Two: The Buildup

You’d Better Be Good

Sure, I Wanna Be Your Dog!

Every Day Is a Blank Page

It’s a Forever Thing

We Were Surrounded and There Was No Way Out

The Divide

Part Three: The Moment

He’s Gone

The Heartbreaker

Sweet Virginia

This Is What I Wanted

Part Four: Cruising

Crossing the Bridge to Washington

Down Under DUI

Life Was Picking Up Speed

Swing Dancing with AC/DC

Inspired, Yet Again

Part Five: Living

Bedtime Stories with Joan Jett

The Daddy-Daughter Dance

The Wisdom of Violet

Conclusion: Another Step in the Crosswalk

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Courtesy of Magdalena Wosinska

Introduction

Turn It Up

Sometimes I forget that I’ve aged.

My head and my heart seem to play this cruel trick on me, deceiving me with the false illusion of youth by greeting the world every day through the idealistic, mischievous eyes of a rebellious child finding happiness and appreciation in the most basic, simple things.

Though it only takes one quick look in the mirror to remind me that I am no longer that little boy with a cheap guitar and a stack of records, practicing alone for hours on end in hopes of someday breaking out of the confines and expectations of my suburban Virginia, Wonder Bread existence. No. Now my reflection bares the chipped teeth of a weathered smile, cracked and shortened from years of microphones grinding their delicate enamel away. I see the heavy bags beneath my hooded eyes from decades of jet lag, of sacrificing sleep for another precious hour of life. I see the patches of white within my beard. And I am thankful for all of it.

Years ago, I was asked to perform at the 12-12-12 Hurricane Sandy relief concert in New York City. Held at Madison Square Garden, it featured the Mount Rushmore of rock and roll lineups: McCartney, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Roger Waters, and countless other household names. At one point, I was approached by a promoter who asked if I would join some of these most iconic artists in the greenroom to take photos with some fans who had donated large sums of money to the cause. Honored to be involved, I happily obliged and made my way through the maze of backstage corridors, imagining a room full of rock and roll history, all standing in an elementary school photo formation, nothing but leather jackets and British accents. As I entered, I was surprised to find only two of the performers, standing at opposite ends of the space. One had the shiny appearance of a brand-new luxury car. Perfectly dyed hair, spray tan, and a recently refurbished smile that had the look of a fresh box of Chiclets (an obvious attempt at fending off the aging process, which ultimately had the adverse effect, giving the appearance of an old wall with too many layers of paint). The other had the appearance of a vintage, burned-out hot rod. Wiry gray hair, deep lines carved into a scowl, teeth that could have belonged to George Washington, and a black T-shirt that hugged a barrel-chested frame so tightly, you immediately knew that this was someone who did not give one flying fuck.

Epiphany may seem cliché, but in a flash I saw my future. I decided right then and there that I would become the latter. That I would celebrate the ensuing years by embracing the toll they’d take on me. That I would aspire to become the rusted-out hot rod, no matter how many jump-starts I might require along the way. Not everything needs a shine, after all. If you leave a Pelham Blue Gibson Trini Lopez guitar in the case for fifty years, it will look like it was just delivered from the factory. But if you take it in your hands, show it to the sun, let it breathe, sweat on it, and fucking PLAY it, over time the finish will turn a unique shade. And each instrument ages entirely differently. To me, that is beauty. Not the gleam of prefabricated perfection, but the road-worn beauty of individuality, time, and wisdom.

Miraculously, my memory has remained relatively intact. Since I was a child, I have always measured my life in musical increments rather than months or years. My mind faithfully relies on songs, albums, and bands to remember a particular time and place. From seventies AM radio to every microphone I’ve stood before, I could tell you who, what, where, and when from the first few notes of any song that has crept from a speaker to my soul. Or from my soul to your speakers. Some people’s reminiscence is triggered by taste, some people’s by sight or smell. Mine is triggered by sound, playing like an unfinished mixtape waiting to be sent.

Though I have never been one to collect “stuff,” I do collect moments. So, in that respect, my life flashes before my eyes and through my ears every single day. In this book, I’ve captured some of them, as best I can. These memories, from all over my life, are full of music, of course. And they can be loud at times.

TURN IT UP. LISTEN WITH ME.

Part One

Setting the Scene

Courtesy of the author’s personal archives

DNA Doesn’t Lie

Courtesy of Kevin Mazur

“Dad, I want to learn how to play the drums.”

I knew this was coming.

There stood my eight-year-old daughter, Harper, staring at me with her big brown eyes like Cindy Lou Who from How the Grinch Stole Christmas, nervously holding a pair of my splintered drumsticks in her tiny little hands. My middle child, my mini-me, my daughter who physically resembles me the most. I had always known that she would someday have an interest in music, but . . . drums? Talk about an end-of-the-trough, entry-level mailroom position!

“Drums?” I replied with eyebrows aloft.

“Yeah!” she squeaked through her toothy grin. I took a moment to think, and as the sentimental lump began to balloon in my throat I asked, “Okay . . . and you want me to teach you?” Shifting in her checkered Vans sneakers, she shyly nodded and said, “Uh-huh,” and a wave of fatherly pride instantly washed over me, along with an enormous smile. We hugged and headed hand in hand upstairs to the old drum set in my office. Like a weepy Hallmark moment, the kind those hyperemotional Super Bowl commercials are made of (the ones that would leave even the hardest monster truck enthusiast crying in their buffalo chicken dip), this is a memory that I will cherish forever.

The moment we entered my office, I remembered that I had never taken any formal lessons, and therefore I had no idea how to teach someone to play the drums. The closest I had ever come to any structured music instruction was a few hours with an extraordinary jazz drummer by the name of Lenny Robinson who I used to watch perform every Sunday afternoon at a local Washington, DC, jazz joint called One Step Down. A tiny old club on Pennsylvania Avenue just outside of Georgetown, One Step Down not only was a hotspot for established touring acts but also hosted a ja

zz workshop every weekend where the house band (led by DC jazz legend Lawrence Wheatley) would perform a few sets to the dark, crowded room and then invite up-and-coming musicians to jam with them onstage. When I was a teenager in the eighties, those workshops became a Sunday ritual for my mother and me. We would sit at a small table ordering drinks and appetizers while watching these musical masters play for hours, reeling in the gorgeous, improvisational freedom of traditional jazz. You never knew what to expect within those bare brick walls, smoke hanging in the air, songs from the small stage the only sound (talking was strictly forbidden). At the time, I was fifteen years old and deep in the throes of my punk rock obsession, listening to only the fastest, noisiest music I could find, but I somehow connected to the emotional elements of jazz. Unlike the convention of modern pop (which at the time I recoiled from, just like the kid from The Omen in church), there was a beauty and dynamic in the chaotic tapestry of jazz composition that I appreciated. Sometimes structured, sometimes not. But, most of all, I loved Lenny Robinson’s drumming. This was something I had never seen before at a punk rock show. Thunderous expression with graceful precision; he made it all look so easy (I now know it’s not). It was a sort of musical awakening for me. Having taught myself to play the drums by ear on dirty pillows in my bedroom, I’d never had anyone standing over me to tell me what was “right” or “wrong,” so my drumming was wild with inconsistency and feral habits. I WAS ANIMAL FROM THE MUPPETS, WITHOUT THE CHOPS. Lenny was obviously somewhat trained, and I was in awe of his feel and control. My “teachers” back then were my punk rock records: fast, dissonant, screaming slabs of noisy vinyl, with drummers who most would not consider traditional, but their crude brilliance was undeniable, and I will always owe so much to these unsung heroes of the underground punk rock scene. Drummers like Ivor Hanson, Earl Hudson, Jeff Nelson, Bill Stevenson, Reed Mullin, D. H. Peligro, John Wright . . . (the list is painfully long). To this day you can hear echoes of their work in mine, with their indelible impression making its way into tunes like “Song for the Dead” by Queens of the Stone Age, “Monkey Wrench” by Foo Fighters, or even Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” (just to name a few). All those musicians were seemingly worlds away from Lenny’s scene, but one thing that they all had in common was that same feeling of beautiful, structured chaos that I loved each Sunday at One Step Down. And that’s what I strove to achieve.

Courtesy of the author’s personal archives

One humid summer afternoon, my mother and I decided to celebrate her birthday by taking in another weekly jazz workshop at the club. It had quickly become our “thing,” one that I still look back on today with fond memories. None of my other friends actually hung out with their parents, especially not at a fucking jazz club in downtown DC, so it made me think she was intrinsically cool and this was another way of strengthening our bond. In the age of Generation X, of divorce and dysfunction, we were actually friends. Still are! That particular day, after a few baskets of fries and a few sets from Lawrence Wheatley’s quartet, my mother turned to me and asked, “David, would you go up and sit in with the band as a birthday present to me?” Now, I don’t remember exactly what my initial response was, but I’m pretty sure it was something along the lines of “ARE YOU OUT OF YOUR FUCKING MIND?” I mean, I had only been playing the drums (pillows) for a few years, and having learned from the old, scratched punk rock records in my collection, I wasn’t anywhere NEAR ready to step up and play JAZZ with these badasses. This was a fantastically unimaginable request. This was being thrown to the lions. This was a disaster waiting to happen. But . . . this was also my mom, and she had been cool enough to bring me here in the first place. So . . .

Reluctantly, I agreed to do it, and slowly got up from our little table, weaving through the packed room of jazz enthusiasts to the coffee-stained sign-up sheet next to the stage. It had two columns: “Name” and “Instrument.” I read through the list of other seemingly accomplished musicians’ names on the list and, with pen shaking in hand, quickly scribbled “David Grohl—drums.” I felt like I was signing my own death warrant. I stumbled back to our table in a daze, feeling all eyes on me as I sat down and immediately started sweating through my ripped jeans and punk rock T-shirt. What had I just done? Nothing good could come from this! The minutes seemed like hours as musician after amazing musician was called up to entertain those hallowed walls and hardened ears. Every one of them could hang with those jazz cats just fine. I became less and less confident with each moment. My stomach was in knots, my palms sweating, my heart racing, as I sat and tried my best to follow the band’s mind-bending time signatures, wondering how on earth I could possibly keep up with the skill of the incredible instrumentalists who graced this stage every week. Please don’t let me be next, I thought. Please, god . . .

Before long, Lawrence Wheatley’s deep baritone drawl came booming over the PA speakers and announced the dreaded words that still haunt me to this day: “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome . . . on the drums . . . David Grohl.”

I tentatively stood to a smattering of applause, which quickly dissipated once the people saw that I was clearly not a seasoned jazz legend, but rather a skinny suburban punk with funny hair, dirty Converse Chucks, and a T-shirt that read KILLING JOKE. The horror in the band’s faces as I walked to the stage made it look as if the Grim Reaper himself were approaching. I stepped onstage, the great Lenny Robinson handed me his sticks as I reluctantly sat on his throne, and for the first time I saw the room from his perspective. No longer sheltered behind the safety of my mother’s table full of snacks, I was now literally in the hot seat, frozen under the stage lights with the eyes of every audience member bearing down on me as if to say, “Okay, kid . . . show us what you’ve got.” With a simple count, the band kicked into something I had never played before (i.e., any jazz song ever), and I did my best to just keep time without fainting in a pool of my own vomit. No solo, no flash, just hold down the tempo and don’t fuck it up. Thankfully, it went by in a flash (sans vomit) and without incident. Unlike most of the other musicians who had performed that day, I had a song that was surprisingly short (though certainly not unintentionally). Imagine that! Done and dusted, I walked away with the relief one feels at the end of root canal surgery. I stood and thanked the band, mouth dry, with a nervous smile, and took an awkward bow. If the band had only known my intention, they would have understood such a desperate act of foolishness. With every ounce of charity in these poor musicians’ hearts, they had unknowingly allowed me to give my mother a birthday gift that she would never forget (to the dismay of about seventy-five paying customers), which meant more to me than any standing ovation I could have wished for. Humbled, I walked back to our little table of hors d’oeuvres in shame, thinking that I had a long, long way to go before I could ever consider myself a real drummer.

That fateful afternoon lit a fire in me. Inspired by failure, I decided that I needed to learn how to play the drums from someone who actually knew what they were doing, rather than stubbornly trying to figure it out all by myself on my bedroom floor. And in my mind, there was only one person to show me how: the great Lenny Robinson.

A few Sundays later, my mother and I returned to One Step Down, and with my naive courage barely summoned, I cornered Lenny on his way to the bathroom. “Umm . . . excuse me, sir. Do you give lessons?” I asked in my best Brady Bunch mumble. “Sure, man. Thirty dollars an hour,” he said. I thought, Thirty dollars an hour? That’s six lawns I’d have to mow in the suffocating Virginia heat! That’s a weekend’s pay at Shakey’s pizza! That’s an eighth of an ounce of weed I’d have to not smoke this week. DEAL. We exchanged phone numbers and set a date. I was well on my way to becoming the next Gene Krupa! Or so I hoped . . .

Our thirteen-hundred-square-foot house in Springfield was nowhere near big enough for a full drum set (hence the ad hoc, makeshift pillow practice set in my tiny bedroom), but for this special occasion I brought in the bottom-of-the-line five-piece Tama kit from my band Dain Br

amage’s practice space, nowhere near Lenny’s caliber of gear. I awkwardly placed the dirty drums in front of the living room stereo and shined them up with some Windex I found under the kitchen sink as I anxiously awaited his arrival, hoping that soon all the neighbors would hear him ripping it to shreds . . . and think that it was me!

“He’s here! He’s here!” I exclaimed as if Santa Claus had just pulled into our driveway. Barely containing myself, I greeted him at the door and invited him into our little living room, where the drums sat shining, still reeking of barely dry glass cleaner. He sat down on the stool, surveyed the instrument, and proceeded to blaze those same impossible riffs that I had seen so many Sundays at the jazz club, a blur of hands and sticks delivering machine gun drumrolls in perfect time. Mouth agape, I couldn’t believe this was happening on the same stretch of carpet where I had spent my life dreaming of becoming a world-class drummer someday. It was finally real. This was my destiny. I was soon to become the next Lenny Robinson, as his riffs would soon become mine.

“Okay,” he said when he finished. “Let’s see what you can do.”

With every ounce of courage I could muster, I launched into my “greatest hits” montage of riffs and tricks that I had stolen from all of my punk rock heroes, crashing and smashing that cheap drum set like a hyperactive child having a full-blown tantrum in an explosion of raw, rhythmless glory. Lenny watched closely and with a stern look quickly realized the amount of work that was going to be required in this gig. After a few cacophonous minutes of disastrous soloing, he stopped me and said, “Okay . . . first of all . . . you’re holding your sticks backward.” Lesson one. Embarrassed, I quickly flipped them around to their proper direction and apologized for such a rookie move. I had always held them backward because I thought the fat end of the stick would produce a much bigger sound when it hit the drums, which proved effective in my brand of Neanderthal pummeling. I didn’t realize it was practically the antithesis of proper jazz drumming. Silly me. He then showed me a traditional grip, taking the stick in my left hand and placing it through my thumb and middle finger, just like all the true drumming greats had done before him, and definitely before me. This simple adjustment completely erased everything I had thought I knew about drumming up until that point, rendering me debilitated behind the kit, as if I were learning to walk all over again after a decade-long coma. As I struggled to keep hold of the stick in this impossible new fashion, he started showing me simple, single-stroke rolls on a practice pad. Right-left-right-left. Slowly hitting the pad to find a consistent balance, over and over again. Right-left-right-left. Again. Right-left-right-left. Before I knew it, the lesson was over, and it was then that I realized at thirty dollars an hour, it was probably cheaper for me to go to Johns Hopkins and become a fucking brain surgeon than to learn how to play drums like Lenny Robinson. I handed him the money, thanked him for his time, and that was that. My only drum lesson.

The Storyteller

The Storyteller